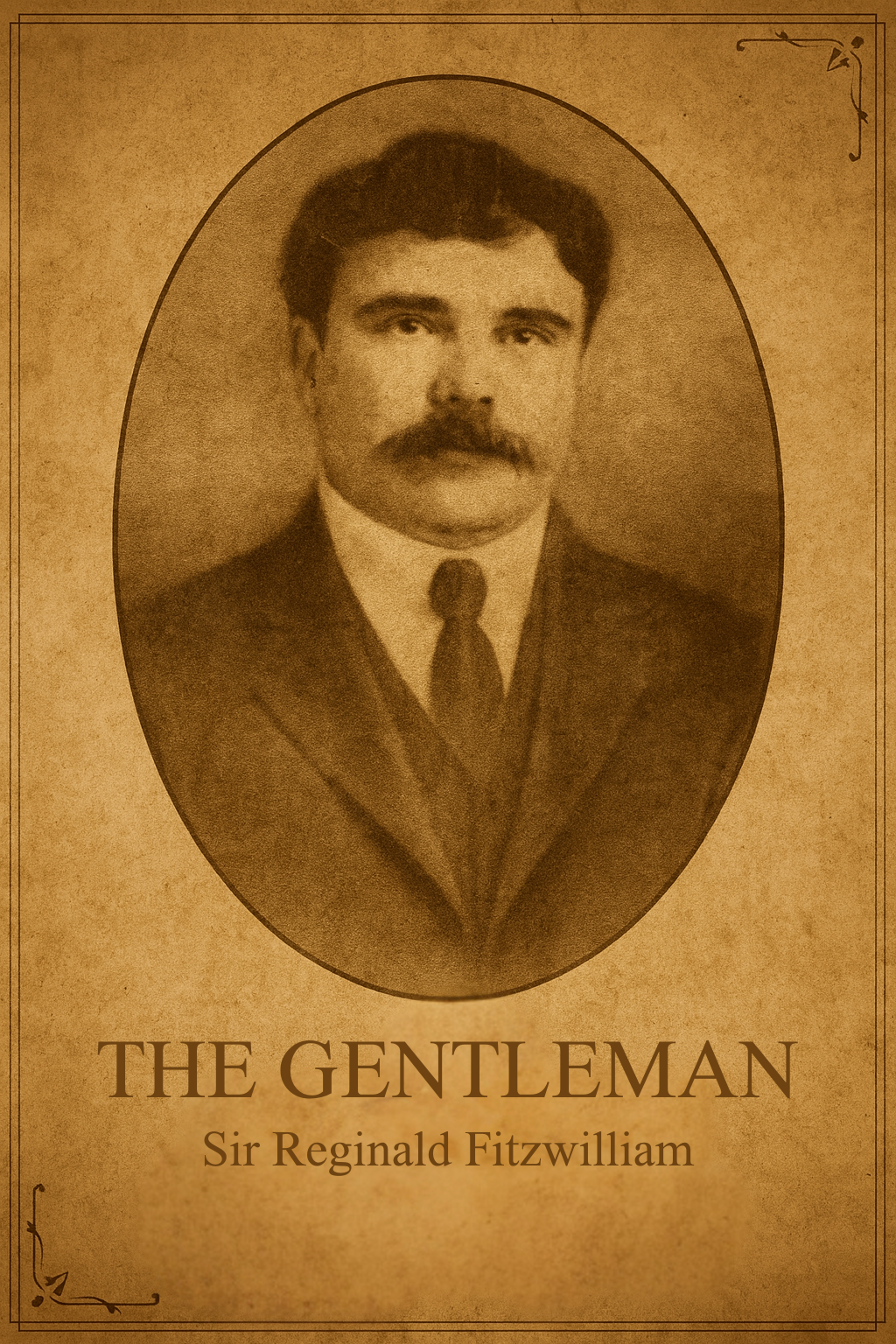

Sir Reginald Fitzwilliam

“The Gentleman”

Sir Reginald Fitzwilliam was a gentleman of the late Victorian age, a man whose name would become synonymous with refinement, discipline, and the pursuit of knowledge along the great arteries of the Silk Roads. Born into an English family of means, Fitzwilliam embodied all the expectations of his station — education at Oxford, service in the cavalry, and a life of polished etiquette. Yet from an early age, he found himself restless, drawn less to the quiet security of estates and more to the whispered legends of caravan trails that stretched across deserts and mountains, binding together the empires of East and West.

His journeys began modestly, with tours of the Continent and the salons of Paris, where he first learned the art of conversation and the rituals of fine tobacco and leather-clad clubs. But soon his appetite grew bolder, and he set his sights eastward. By steamship, rail, and camel caravan, Fitzwilliam traced the spine of the ancient trade routes — from Constantinople through Persia, to the domes and bazaars of Samarkand, and onward to the tea houses and lacquered halls of China.

Wherever he traveled, he carried himself as both observer and participant. He sat at the firesides of caravan masters who told stories of storms on the Taklamakan, he studied with Sufi mystics who spoke of discipline as a mirror of the soul, and he lingered in monasteries perched above the Pamirs where the thin air carried the scent of juniper and resin. His journals, written in a fine, deliberate hand, describe not just landscapes and ruins but the small refinements of daily life — the oils pressed in Kashgar, the resins traded in Herat, the cherry blossoms admired in Kyoto.

To Fitzwilliam, grooming was a universal language. He noted how merchants perfumed their garments before entering negotiations, how scholars anointed their beards with fragrant oils before reciting poetry, how warriors burnished their boots and belts until they gleamed like bronze. To him, these rituals of presentation were as essential as treaties or trade agreements. He believed that the order of one’s appearance reflected the order of one’s mind.

In his later years, Fitzwilliam returned to England, his trunks laden not with treasure but with notebooks, sketches, and recipes gathered from across continents. He became a fixture of London’s social clubs, those sanctuaries of leather-backed chairs, heavy drapery, the aroma of tobacco smoke, and the crackle of a fire. It was there, among fellow travelers, officers, and scholars, that he began to share his vision: a fellowship devoted to preserving the art of refinement as practiced along the Silk Roads.

This fellowship became known as the Royal Grooming Society. Within its circles, Fitzwilliam was regarded not simply as a founder but as a philosopher of presentation. His presence was unmistakable: seated by the fire, pipe in hand, the faint scent of smoke and polished leather surrounding him like an aura. His colleagues said that when Sir Reginald entered a room, he brought with him the essence of every journey he had ever taken.

Though the details of his final years are uncertain, his portrait endures as the Society’s emblem. In his steady gaze, one can almost smell the tobacco of London clubs, the leather of saddlebags carried across deserts, and the lingering smoke of campfires along the Silk Road. His scent — Gentleman’s Drawing Room — captures that legacy, a tribute to evenings spent in conversation, reflection, and the enduring bond between elegance and exploration.