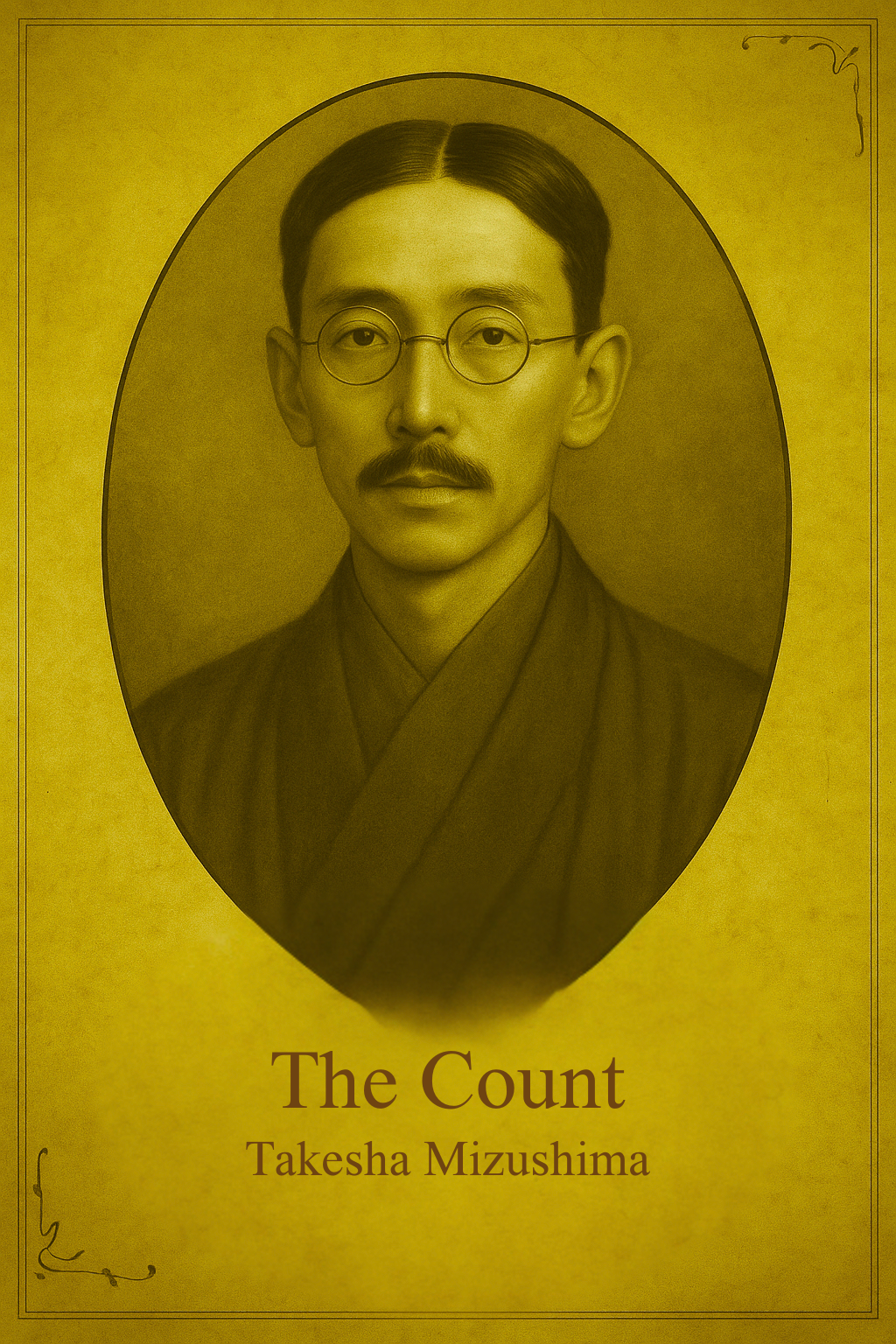

Takeshi Mizushima

“The Count”

Count Takeshi Mizushima was born into a family of samurai lineage in Kyoto during the twilight of the 19th century, but it was in Nara that he chose to establish his seat. The ancient capital, once the eastern terminus of Silk Road exchange, stood for him as both sanctuary and crossroads — a place where the teachings of Buddhism, the fragrance of spices, and the artistry of lacquer and silk first entered Japan through continental caravans. Mizushima believed that to live in Nara was to live at the threshold of the world, close to the roots of his own heritage yet always facing outward toward the great highways of Asia.

Raised amid the quiet rituals of Buddhist temples, he was taught discipline through incense ceremonies, calligraphy, and meditation. But his imagination was set ablaze by the stories of monks and merchants who centuries earlier had carried scrolls, resins, and blossoms along the trade routes that stretched from Chang’an to Persia. Nara, with its great wooden halls and guardian statues, whispered to him of those connections. For Mizushima, the deer roaming the temple precincts were not merely sacred messengers but living symbols of the constant flow between cultures — gentle yet enduring, like the exchanges that had bound Japan to the Silk Roads.

From this seat in Nara, Mizushima embarked on his journeys. His writings describe leaving the lantern-lit streets of the city and traveling westward — through Korea, across the steppes of Central Asia, into the domes and bazaars of Samarkand. Wherever he went, he carried Nara with him: the scent of cherry and almond blossoms that drifted each spring across temple gardens, the memory of sutras chanted in low voices, the image of lacquered halls glimmering in twilight. These impressions mingled with the spices of Bukhara, the smoke of Kashgar, and the resin of Herat, binding East and West not just in trade but in fragrance and ritual.

In the Royal Grooming Society, he became known simply as The Count. His colleagues recalled how he spoke of Nara as a “mirror city” of the Silk Road — both a culmination and a beginning, a place where refinement was born from centuries of exchange. Seated in his study in Nara, spectacles gleaming in lamplight, the faint aroma of blossoms and almonds surrounding him, he seemed less a man than a bridge between civilizations.

Though many of the treasures he safeguarded remain hidden, his legacy is carried in the Society’s traditions. His scent — Nara in Spring — recalls the almond and cherry blossoms that stirred in temple gardens, blending with the memory of distant caravan trails. It is a fragrance of passage and return, of Nara and the Silk Road intertwined, and of a life devoted to the quiet dignity of refinement and ritual.